Battle of Chalgrove Field

Battle of Chalgrove 18th June 1643

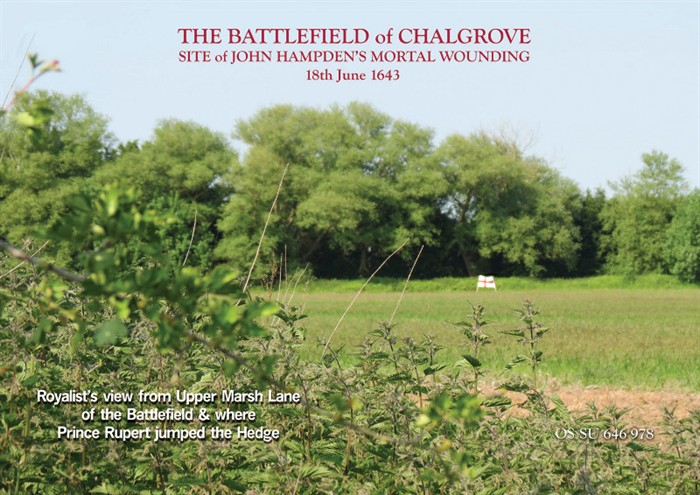

Battlefield Site OS SU648978

In April 1643 the Earl of Essex, Lord General of Parliament's Army, assembled a force of 16,000 foot, 3,000 cavalry and a siege train to re-take Reading; a town of strategic importance as goods coming down the River Thames from the west to London could be controlled.

The siege endured for 10 days until Col John Hampden and Col John Urry's regiments stormed the ramparts and after a stiff fight took Reading. They found the inhabitants diseased, probably with cholera and typhoid. Essex's army, living rough in the fields around Reading enduring cold wet insanitary conditions had also succumbed to 'camp fever'.

The King's H/Q at Oxford was virtually defenceless being short on all the necessities to make war or even to defend the town. Parliament's forces were also aware of the royalists' predicament yet Essex chose to keep his army in and around Reading for another month before marching to Thame : a manoeuvre designed to block the road to London.

Death, disease and desertion depleted Essex's army. The King received many senior parliamentarian officers at Oxford, who brought with them arms and disaffected men. Most importantly these senior officers brought intelligence of the state of Essex's army and its deployment in and around Thame. They even had knowledge of a pay wagon, reputably containing £21,000, coming to Thame. The scene was set for Prince Rupert to make a daring raid to exploit Essex's weaknesses and to destroy his faltering military reputation.

On June 17th 1643 Essex sent 2,500 men to probe and weaken the royalist defences around Islip to gain a foothold to attack Oxford. They were seriously rebuffed without a shot being fired. Parliament's forces retired back to Thame and Chinnor.

The March to Chalgrove via Chinnor

Col John Urry, a recent turncoat, was at Prince Rupert's side as they watched Parliament's army march away to Thame. Urry reminded the Prince of the enemy's quartering and that the pay wagon was due into Thame the following morning. He highlighted that many of those who had viewed Islip were from Chinnor. Rupert ordered his men to be on Magdalen Bridge ready to march by 4 pm. Their objective was to march through the night and attack Essex's furthermost outpost, Chinnor.

Rupert's army of over 2,000 men marched out of Oxford heading to Chiselhampton Bridge. It consisted of 500 musketeers, 500 dragoons and 1,000 cavalry comprising of three crack regiments and the Prince's Lifeguard.

Refreshed after resting until night fall at Chiselhampton they set off into the night passing through the quiet lanes. At Tetsworth sentries fired at them as they passed. At Postcombe Col. Morley's troop fled leaving a few sleepers in the barns to be captured with their arms and a Standard.

By 5am the royalists had surrounded Chinnor. The new levies, back from Islip, who had not long before found their beds, were caught naked in their quarters. Some brave soldiers fired their muskets from the windows, but were killed as they ran from the blazing thatch buildings that had been torched.

Rupert set off back down the Icknield Way laden with booty, 120 prisoners and 50 dead littering streets amongst the flames that was Chinnor.

Gunter, Crosse and Sheffield's troops, about 200 cavalrymen, watched as the royalist army passed Aston Rowant. These brave troops harried the rear of the royalists in the hope of slowing their march in the expectation of reinforcements from Thame.

At South Weston 100 dragoons from Thame joined Gunter's men and together they skirmished heavily with the royalists. Essex's letter to the House of Commons the next day stated that this encounter was the Battle. He wrote that, 'not having more than 300 men they fought bravely', against the 2,000 royalists, but were routed; the origin of the story that the Battle of Chalgrove was a skirmish.

At Stokefield John Hampden, Col. Dalbier and Sir Samuel Luke, on their way to Watlington, met with Gunter's men. It is likely that Hampden was about to appoint Luke and Dalbier as his senior officers. It is also likely that a chest of money was sent ahead to Watlington for Hampden to pay his Regiment. The chest was never called for as Hampden was mortally wounded at Chalgrove. Robert Parslow landlord of the Hare & Hounds became a benefactor to Watlington.

Battle Plan - At Clare Crossroads a scratch force of 800 cavalrymen from Thame met with Hampden & Gunter's men. They quickly formed a plan to outflank the royalists. Gunter's men harried the royalists' rear through Easington while the Thame force went over Golder Hill into a Great Close, Lewknor Meadow. From the bottom of Golder Hill they could see their enemy behind a Great Hedge. A Great Hedge separated parishes and was a formidable barrier designed to stop livestock from straying. The royalist cavalry standing in a Chalgrove cornfield just stood and watched the confusion from the Chalgrove side of the Great Hedge as Gunter tried to form his men into battle order.

Rupert had sent his infantry with the prisoners on ahead with the dragoons to protect them and away from danger. With his enemy unprepared for battle Rupert ordered his cavalry to march away out of the Chalgrove cornfield. Another myth broken, the battle did not occur in a Chalgrove cornfield.

Unable to penetrate the Great Hedge parliament's men galloped off down the Close following the Great Hedge until they reached the gap made by Warpsgrove Lane's access to Warpsgrove House.

Eight troops of Horse, 560 men, rode through the gap onto the battlefield and challenged the royalists' right flank unaware that they had marched into Prince Rupert's trap. Reserves of five troops, 350 men, were left near the gap in Warpsgrove Lane in the trees by Warpsgrove House.

The Battle

Essex's forces were trapped. Once on the Battlefield their only way to retire was back through the gap in the Great Hedge. Their reserve, a third of their force, could only assist on the battlefield if they could get through the gap. Rupert ensured by clever deployment that Parliament's reserves would remain spectators, their forces divided.

The Great Hedge at their rear and a deep bog to the west with scrubby hedges along Warpsgrove Lane that would impede any rout determined they had to fight. The Prince had formed up in Upper Marsh Lane behind a sparse hedge hemming in their opponents and ready to confront the enemy.

Rupert jumped the hedge and his Regiment and Lifeguard jumbled over after him. They charged swords drawn straight at the enemy taking pistol shot first at a distance and then at closer quarter. The royalists with loaded pistols selected their targets and fired at point blank range taking a terrible toll. All 1,000 of Rupert's forces had the freedom of the battlefield, being able to retire and reload their pistols at will. Being outmanoeuvred and outnumbered by nearly two to one by three crack regiments and Rupert's hand picked Lifeguard and unable to rout or call in the Reserves their fate was clear.

Rupert's men captured 80 men of quality from Chalgrove and it was reported in the Mercurius Aulicus, a royalist newspaper printed a day after the Battle and not denied by Essex, that '100 were killed here in this place'.

The battle raged for over an hour and the royalists who had been in the saddle for 18 hours were exhausted their horses tired. Rupert ended the battle by rounding up the desperate parliamentarian cavalry and forced them through the gap disrupting their reserves. The reserves and troopers were all chased back over Golder Hill from whence they came.

Over Golder Hill the routed men met Sir Philip Stapleton's cavalry regiment who had ridden out from Thame. Prince Rupert master of Chalgrove held the battlefield for half hour, but as no more action was forthcoming he turned for Oxford.

Prince Rupert's Triumph

The news of his triumph went before him and at 2pm Rupert rode into Oxford to a heroes welcome. The 200 prisoners, horses, arms and other military equipment and most importantly 9 Colours, including three from the Earl of Essex's regiment, underlined his success.

Essex's reputation as a General was shattered and his army demoralised. They left Chalgrove leaving London open to attack, but the royalists did not have the firepower to march on London.

Exhumation

John Hampden, who had put himself in Captain Crosse's troop as a trooper was shot in the back with two carbine balls. (The site of the mortal wounding is discerned to be close to OS SU648978, see image) The myth that Hampden's pistol exploded was a slander written probably under the orders of Sir Robert Walpole in 1721. The exhumation at Great Hampden Church in 21st July 1828 was undertaken by Lord Nugent to resolve this issue. They exhumed John Hampden's father's tomb so the findings were meaningless. See, 'The Controversy of John Hampden's Death' - Derek Lester & Gill Blackshaw ISBN 0-9538034-0-6 for the full story.